GORD and Hiatus Hernia

Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD) and hiatus hernias are often discussed together because they are frequently related and treated similarly. However, they are distinct conditions. A hiatus hernia is an anatomical abnormality in which the stomach moves upwards through an opening in the diaphragm, while GORD is a disorder involving the malfunction of the anti-reflux valve at the bottom of the oesophagus. While a hiatus hernia often contributes to GORD by affecting the function of the reflux valve, it’s possible to have GORD without a hiatus hernia, and vice versa.

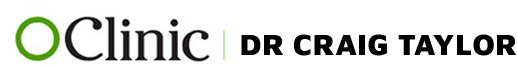

What is GORD?

GORD stands for Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease, a condition in which stomach fluids—comprising hydrochloric acid, pepsin, pancreatic enzymes, and bile—flow backward into the oesophagus, causing irritation. This happens primarily for two reasons:

- The anti-reflux valve at the bottom of the oesophagus isn’t functioning properly.

- The oesophagus’ ability to clear the refluxed fluids (peristaltic clearance) is impaired.

In some cases, GORD may also occur in people with a normally functioning reflux valve and oesophageal clearance, but whose oesophageal lining is unusually sensitive to these fluids.

While the stomach lining is designed to withstand the corrosive nature of these fluids, the more delicate lining of the oesophagus is not. This leads to irritation, commonly felt as heartburn — a burning sensation behind the breastbone that may feel like it’s rising up the chest. Certain foods (rich, spicy foods, chocolate, caffeine, and alcohol) can aggravate symptoms by relaxing the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES), and symptoms can also worsen when bending over or lying down at night, when gravity’s effect is lost.

What is a Hiatus Hernia?

A hiatus hernia occurs when the upper part of the stomach bulges through the natural opening in the diaphragm called the hiatus. Normally, only the oesophagus passes through this opening, which connects to the stomach below the diaphragm. Unlike other hernias, a hiatus hernia is internal and cannot be seen or felt from the outside.

While most hiatus hernias are small and asymptomatic, larger hernias can lead to several complications:

- GORD: The most common consequence of a hiatus hernia, as it can displace the reflux valve, disrupting its normal function and leading to reflux.

- Regurgitation: The dysfunction of the reflux valve can also lead to regurgitation of stomach contents.

- Swallowing Difficulties: A hernia can distort the connection between the oesophagus and the stomach, making swallowing difficult.

- Shortness of Breath: When the stomach herniates into the chest, it can compete for space with the lungs, activating pressure receptors that cause shortness of breath. This can also affect blood flow to the heart, potentially exacerbating fatigue or heart failure.

- Gastric Volvulus and Obstruction: In severe cases, a large hiatus hernia can twist, causing a gastric volvulus or obstruction, which is a medical emergency.

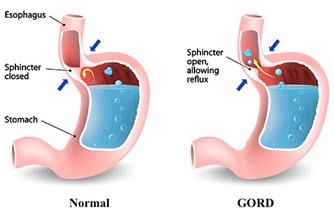

Types of Hiatus Hernia

There are three main types of hiatus hernias:

- Sliding Hiatal Hernia (Type 1): This is the most common type, where the junction between the oesophagus and stomach moves up into the chest through the hiatus. This often leads to GORD due to disruption of the reflux valve.

- Paraesophageal Hiatal Hernia (Type 2): Less common but more serious, this hernia occurs when part of the stomach squeezes up through the hiatus while the oesophagus remains in its normal position. It can lead to swallowing difficulties or even strangulation of the stomach, which may cause ulcers and bleeding.

- Mixed Hiatal Hernia (Type 3): This involves elements of both sliding and paraesophageal hernias.

- Type 4: When other abdominal organs, such as the colon or small intestine, protrude through the hiatus, it is classified as a type 4 hernia.

What Are the Dangers of GORD?

Although common, GORD should not be dismissed as a trivial issue. Repeated acid exposure can lead to inflammation and damage of the oesophagus, a condition called oesophagitis. Depending on the severity, oesophagitis can be classified into different grades seen through endoscopy. Persistent reflux can also cause complications such as:

- Chronic Cough and Voice Hoarseness: If the reflux reaches the throat, it can irritate the larynx.

- Dental Decay: Acid from reflux can erode tooth enamel.

- Aspiration Pneumonia: Refluxed material can enter the lungs, leading to infections.

- Strictures and Scarring: Chronic inflammation can lead to narrowing of the oesophagus, making swallowing difficult.

- Anaemia: Ongoing bleeding from damaged tissue can result in anaemia.

- Barrett’s Oesophagus: This condition, caused by chronic inflammation, can lead to cellular changes in the oesophagus that may increase the risk of oesophageal cancer.

How is GORD Investigated?

Diagnosis starts with a detailed review of symptoms, including heartburn, swallowing difficulties, regurgitation, cough, or hoarseness. Factors that trigger or relieve symptoms, such as specific foods or medications, are also considered.

To confirm the diagnosis, several tests may be used:

- Upper Endoscopy: This allows the doctor to directly observe the oesophagus, check for signs of inflammation, and assess for a hiatus hernia.

- pH Impedance Monitoring: This test measures the presence of stomach acids in the oesophagus.

- Manometry: Used to assess the function of the lower oesophageal sphincter and oesophageal clearance mechanisms.

- Reflux Isotope Scan: Helps identify laryngo-pharyngeal reflux.

- Imaging Tests: Ultrasound, CT scans, and other investigations may be used to assess related conditions or complications.

How is GORD Treated?

Treatment depends on the severity of the condition:

- Mild Cases: Lifestyle changes such as avoiding trigger foods, eating smaller meals, not lying down after eating, and using over-the-counter antacids like Mylanta or Gaviscon can be effective.

- Frequent or Severe Cases: Acid-suppressing medications like Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) (e.g., Losec, Nexium, Somac, Pariet) are commonly prescribed. While effective for controlling symptoms, PPIs do not address the underlying cause of reflux and come with potential long-term risks, such as gastrointestinal infections, osteoporosis, kidney disease, and nutrient deficiencies.

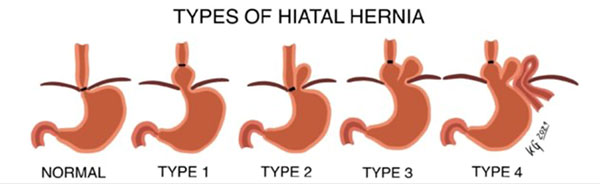

- Surgical Treatment: For patients with persistent symptoms despite medication, laparoscopic fundoplication—a minimally invasive surgery—is often recommended. This procedure involves wrapping the top of the stomach around the lower oesophagus to improve the function of the reflux valve.

How is a Hiatus Hernia Treated?

Surgical treatment for a hiatus hernia is typically the same as for GORD, using laparoscopic fundoplication. The surgery not only corrects the anatomical defect but also helps improve the function of the anti-reflux valve.

Risks and Side Effects of Laparoscopic Fundoplication Surgery

Laparoscopic fundoplication is generally considered a safe procedure with minimal risk. However, like all surgeries, it carries some risks, including:

- Bleeding, infection, blood clots, and adverse reactions to anesthesia.

- Long-term issues like gas bloat, where it becomes difficult to release swallowed air, causing abdominal bloating and increased flatulence.

- Difficulty swallowing tougher foods, such as steak or bread.

Modern approaches, such as the Toupet Fundoplication, which uses a partial wrap, are designed to minimize these side effects by allowing the reflux valve to function more naturally, while providing excellent reflux control.

Recovery and Return to Work

The Laparoscopic Fundoplication procedure typically takes about one hour and is usually followed by an overnight stay in the hospital. Patients are generally discharged by 10 AM the next day. Most of the recovery takes place within the first three days, during which we recommend staying at home to rest.

Since this procedure is minimally invasive, using keyhole surgery, it is usually not very painful. To further enhance your comfort, we inject a long-acting local anesthetic into the abdominal wall, which helps to numb the area and ease movement during recovery. Some patients may experience referred shoulder pain, particularly on the left side, known as "gas pain". This is a common occurrence after laparoscopic procedures and typically resolves within a couple of days. Heat packs or gentle massage can help alleviate this discomfort.

If you’re recovering well and feel up to it, you can resume driving and return to light daily activities after three days. For those with less physically demanding work, returning to work is possible after 5–7 days. However, if your job involves heavy lifting or strenuous physical tasks, we recommend waiting at least two weeks before returning.

To allow the gastro-oesophageal area to heal properly, you’ll need to follow a gradual diet progression. Initially, you’ll start with a liquid diet, then transition to pureed foods after 1-2 weeks. A full, normal diet can typically be resumed after 4 weeks.

- Swimming can be resumed after 3 weeks.

- Gym activities, including weightlifting, Pilates, and resistance training, should be avoided for 6 weeks to ensure optimal healing.